From The Kinks to the Police, from Parliament-Funkadelic to Fleetwood Mac, here’s another 25 of the 100 greatest Rock bands of all time (numbers 75–51). If you’re new here, be sure to check out the series introduction where I lay out what qualifies a band for inclusion on this list (be a band; be excellent; be successful; or be influential!). I also describe my unavoidably personal ranking methodology and explain why I include rap, soul, and vocal groups in a list of “rock bands.”

Otherwise, jump right to the ranking.

See Who Else Makes the List…

What is Rock?

Simply stated, Rock Music formed the basic DNA of popular music from about 1960 to 2000.

The 1950s are fondly remembered as The Golden Age of Rock and Roll. Much of what we would call Rock and Roll—Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, etc.—is firmly rooted in the blues, gospel, country, and R&B which came before it. But when these sounds merged—and most importantly, when the line separating Black and white music blurred—the cultural phenomenon known as rock and roll engulfed America’s youth.

Then, in 1959, a series of unfortunate events signaled an end to this era, including Elvis Presley’s draft into military service, Little Richard’s departure into the priesthood, and the tragic airplane crash that claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper.

Rock and Roll had reached its first low ebb, leaving popular music in the well-manicured hands of treacly teen idols like Frankie Avalon and Fabian. Rock and Roll had many critics, including an outspoken contingent of segregationists who decried the spread of so-called “jungle music.” Those who thought of rock and roll as coarse, vulgar, and little more than a teen-fueled fad were vindicated. Rock and roll was dead.

Then the Beatles and Stones washed ashore in 1964. A year later, Bob Dylan plugged his guitar into an amp at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival; Motown beamed the Detroit sound into every dancefloor in America; Brian Wilson took the Beach Boys into unchartered waters; the Grateful Dead tried LSD for the first time; and Bruce Spingsteen’s mother took out a loan to buy her kid his first guitar.

Rock and Roll was reborn, but with a harder edge, a more adventurous spirit, and substantially longer hair. It was in this moment that Rock and Roll became “rock”—something less formulaic, less immediately definable, and far more expansive. It became something more than some guitars and a drum kit. Rock became a palette of infinite colors inspiring boldness, experimentation, and the total deconstruction of barriers.

Rock is the catch-all terminology for everything that came after the first Golden Age—British Invasion, Girl Groups, Motown, Greenwich Village, Psychedelia, Progressive Rock, Soul, R&B, Metal, Punk, New Wave, Disco, Funk, Hip Hop, Alternative, and even Rock and Roll. So when we call something a “rock band,” let’s try to avoid any hangups about what we think ‘rock’ should sound like. Avoiding exactly those kinds of preconceived notions is what helped the artists on this list to earn our esteemed recognition, not to mention many lesser honors like unspeakable wealth and enshrinement in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Ok. You get the point. Rock is everything. Everything is rock.

Qualifications For Inclusion

- Be a Band

First, in order to be considered one of the 100 Best Rock Bands of All Time, one must be a band. Any group of people who play instruments, write songs, and perform concerts together qualifies as a band. Sooooo, for instance, Hootie & the Blowfish would qualify as a band. Wait. Come back. That’s just an example. They’re not on the list. Also qualifying for inclusion here are duos, vocal combos, rap crews, house bands, and whatever you’d call the colorful mass of humans that comprise Parliament/Funkadelic. Not eligible for inclusion are solo artists, which explains the conspicuous absence of Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Rick Astley.

- Be Born After 1955

Also not eligible are bands whose output generally predates the proliferation of rock and roll. R&B groups like Billy Ward and his Dominos and vocal combos like the Ink Spots have an unquestionable place of importance in the early development of rock and roll. But there is an invisible line in history that bisects at the point where Elvis Presley first came to national prominence in 1955. Thus, only those who achieved their greatest musical accomplishments thereafter may be considered.

- Be Excellent;

Of course, everything I just said does nothing to prevent Hootie & the Blowfish from making the list. This is why our next qualification is critical. The top qualification for inclusion here is musical, instrumental, and/or artistic excellence. Bands included here helped raise the standards of songcraft, live performance, studio ingenuity, or virtuosity. Sometimes, artistic excellence is universal enough to transcend subjectivity. For instance, if you make a Top 100 list that doesn’t include Pink Floyd, it must be because Roger Waters ran over your dog. Otherwise, the consensus is that they were pretty darn excellent. The same is true of nearly all the artists included here.

- Or Be Successful;

I admit that not every band on this list is inherently excellent. But some bands are simply too successful to miss the cut. Some bands sold so many records that, no matter what you or I think of them, neither of us could deny their impact on popular culture. Yes, the Eagles are on this list. Yes, I recognize that they could be insufferably smug. But really, there’s just no way a band could sell 150 million records without doing a lot of things really right.

- Or Be Influential

Some artists on the list may defy any conventional definition of excellence or success, but must be ranked for the cultural impact of their work. Sid Vicious was such a crummy musician that his fellow Sex Pistols would famously turn down the volume on his amp during live performances. But the depraved bassist also perfectly embodied the nihilism and rage that made his band monumentally influential. In order to be included on this list, being excellent helps. But if you don’t have that, making an earth-shattering impression on the course of history is the next best thing.

Ranking

Our ranking procedure was extremely scientific in that I wore a lab coat and safety goggles.

Consistent with our broader mission here at Music Influence, the goal was to rank artists by influence. When we rank one artist above another, we are not making the argument that the former artist is better than the latter. Instead, we’re arguing that the higher-ranking artist is more influential. Thus, when we place hip hop pioneers Run D.M.C. ahead of alt-radio godfathers R.E.M., we are not arguing that Run D.M.C. is better. Instead, we are claiming that the Hollis, Queens trio did just slightly more to change the face of popular music than did the quartet out of Athens, Georgia.

That said, unlike other rankings on our site, this list isn’t powered by our algorithm. Instead, influence is informed by a set of unweighted variables including commercial success, artistic importance, cultural relevance, and personal preference. Yeah, that’s right, there’s some bias in here. If you don’t like it, write your own list. Seriously. I’m not being pithy. It’s a really fun exercise and I wish you the best.

But this is my list so you’re bound to disagree with some of my choices. You probably think I’m crazy to rank this band over that band. You might think I’m an idiot for ranking a band you hate ten spots above a band that you’d sell a kidney (perhaps even your own) to see live. You might wish to send me hate mail for failing to find the space in 100 entries and 50,000+ words to even mention the band that you’ve dedicated your adult life to worshiping. (Rush fans—please direct your Dr. Who-reference-riddled diatribes directly to our webmaster).

Well that’s the beauty of a list like this. There’s no way it’s going to be 100% right but you can’t prove it’s wrong. This means we get to have a fantastic and impossible-to-settle debate about rock music, about what it is, where it’s been, and where it’s going.

Enough introducing. Let’s get right into the bands.

The Best Rock Bands of All Time: 50-26

50. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers enjoyed a 30 year run on the charts without ever embarrassing themselves. The Dylanesque shit-kicker and his highly underrated band never sacrificed integrity for airplay but they had it by the truckload anyway.

Emerging from the college scene in Gainesville, Florida, Petty first partnered with future bandmates Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench in Mudcrutch. Mudcrutch earned some local popularity before breaking up in 1974. After two years of unfruitful solo work, Petty rejoined his old mates, along with Stan Lynch and Ron Blair, to form the Heartbreakers.

The band scored a deal with Shelter Records and released their eponymous debut. Their ragged look and tight rockers led radio programmers and promoters to lump the Heartbreakers in with the emergent punk movement. While the album has some of that three-chord fire, it was far more tuneful and indebted to Southern jangle than was most punk. Anchored by “Breakdown” and the quintessential, windows-down tragedy of “American Girl,” Petty’s debut offers a disc of power pop with a straight-from-the-garage attitude.

With their second record, You’re Gonna Get It, the Heartbreakers successfully revisited the formula (and the hit-to-filler ratio) of their debut. But on their third record, they created a glorious masterpiece overflowing with 70s rock radio staples. Damn the Torpedoes is the perfect symbiosis of hook-craft and album-oriented songwriting. In addition to the songs you already know (“Refugee,” “Here Comes My Girl,” “Even the Losers,” “Don’t Do Me Like That”), album tracks like the bar band kissoff “What Are You Doin’ In My Life?” and the reflective “Louisiana Rain” revealed Petty’s growing consistency as a songwriter as well as the all-too-frequently overlooked fretwork of guitarist Mike Campbell.

Over the course of the 1980s, Petty and the Heartbreakers would become among the most reliable recording units in the game, as well as frequent contributors to MTV’s growing inventory of videos. They also occupied a high profile spot as the touring band for one Bob Dylan. Petty subsequently joined Mr. Zimmerman (along with George Harrison, Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne) to form the Traveling Wilburys in 1988.

Petty emerged from these experiences with some powerful new friends and his most compelling lyrics yet. Fortunately, if Dylan’s songwriting had rubbed off on Petty, his late ’80s “singing” had not. Full Moon Fever (1989) offered Petty’s strongest vocals to date, with “Yer So Bad” and “Free Fallin’” displaying a richer and more contemplative voice. Full Moon Fever moved Petty into the next echelon of rockers both commercially and critically.

There, Petty remained for the next 25 years, touring with his faithful backing band and releasing an endlessly uncompromising series of records that earned the Heartbreakers a 2002 ticket into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Petty and company continued to notch new successes over the next decade+. Indeed, with 2014’s Hypnotic Eye, the band which had sold more than 80 million records worldwide enjoyed its very first chart-topper.

Sadly, just one week after returning from the band’s 40th anniversary tour, and two weeks shy of his 67th birthday, Tom Petty died of an accidental drug overdose in 2017.

Photo By: ABC/Shelter Records – eBayfrontback, Public Domain

49. The Ventures

The Pacific Northwest is noted for its uniquely fertile musical landscape, from Jimi Hendrix to Nirvana. But the first group to really put Washington state on the rock and roll map was the Ventures. The Ventures are, without competition, the single most successful instrumental rock group of all time. These Tacoma, Washington natives deserve credit for never diverting from their proven formula of guitar-heavy, pop-oriented, wordless rock and roll. Though their reputation precedes them as a definitive surf rock group, they truly dabbled everywhere, from film score material to dance crazes, from hot rod to exotica. Even as their lineup shifted almost constantly from the band’s 1958 inception, its core instrumental mission has been a constant.

The Ventures began around Don Wilson (guitar), Bob Bogle (bass), and Nokie Edwards (guitar). Skip Moore would be the first of several players to occupy the seat behind the drum kit but would be replaced by Howie Johnson just after the recording of the group’s debut single, “Walk, Don’t Run.” The Ventures would transform the old Johnny Smith jazz tune into a reverb-heavy, vibrato-soaked nugget that, in 1960, reached #2 on the Billboard charts. The first surf rock hit, it would help touch off a craze that saw the tubular genre achieving mainstream popularity as far inland as Minnesota (which birthed The Trashmen of “Surfin’ Bird” fame).

For the next two years, the Ventures capitalized on the cresting surf rock wave with a series of popular 45s, spawning legions of imitators. Nokie Edwards’ smoking leads were particularly vulnerable to copycatting. In 1962, Howie Johnson would be replaced by Mel Taylor, producing what is largely considered the Ventures’ classic lineup. It was at this juncture that the group unwittingly positioned itself as an innovator in the popularization of the long player.

Moving their focus from singles to full length records, albums like The Ventures Play the Country Classics (1963), The Ventures in Space (1964), and The Ventures a Go-Go (1965) saw the band striking out on various thematically and musically cohesive genre experiments, imbuing each with their signature grooviness. In addition to becoming a favorite listening experience for an emergent collecting demographic known as audiophiles, The Ventures were gaining tremendous fame on the international market.

Benefiting from the fact that their music presented no language barriers, the Ventures became, and remain, one of the most popular acts in the history of Japan, even occupying five of the top ten chart positions in 1965. Like many of their fellow rock and roll pioneers, the Ventures saw slipping sales and relevance by the 1970s and settled into the nostalgia circuit with an ever-changing cast of musicians. With the passing of Nokie Edwards in 2018, the touring act that currently utilizes the Ventures name contains no original members. However, with more than 100 million records sold and a Hall of Fame induction in 2008, the Ventures defined, expanded, and proliferated instrumental rock and roll.

Photo By: Liberty Records – Billboard, page 11, April 29, 1967, Public Domain

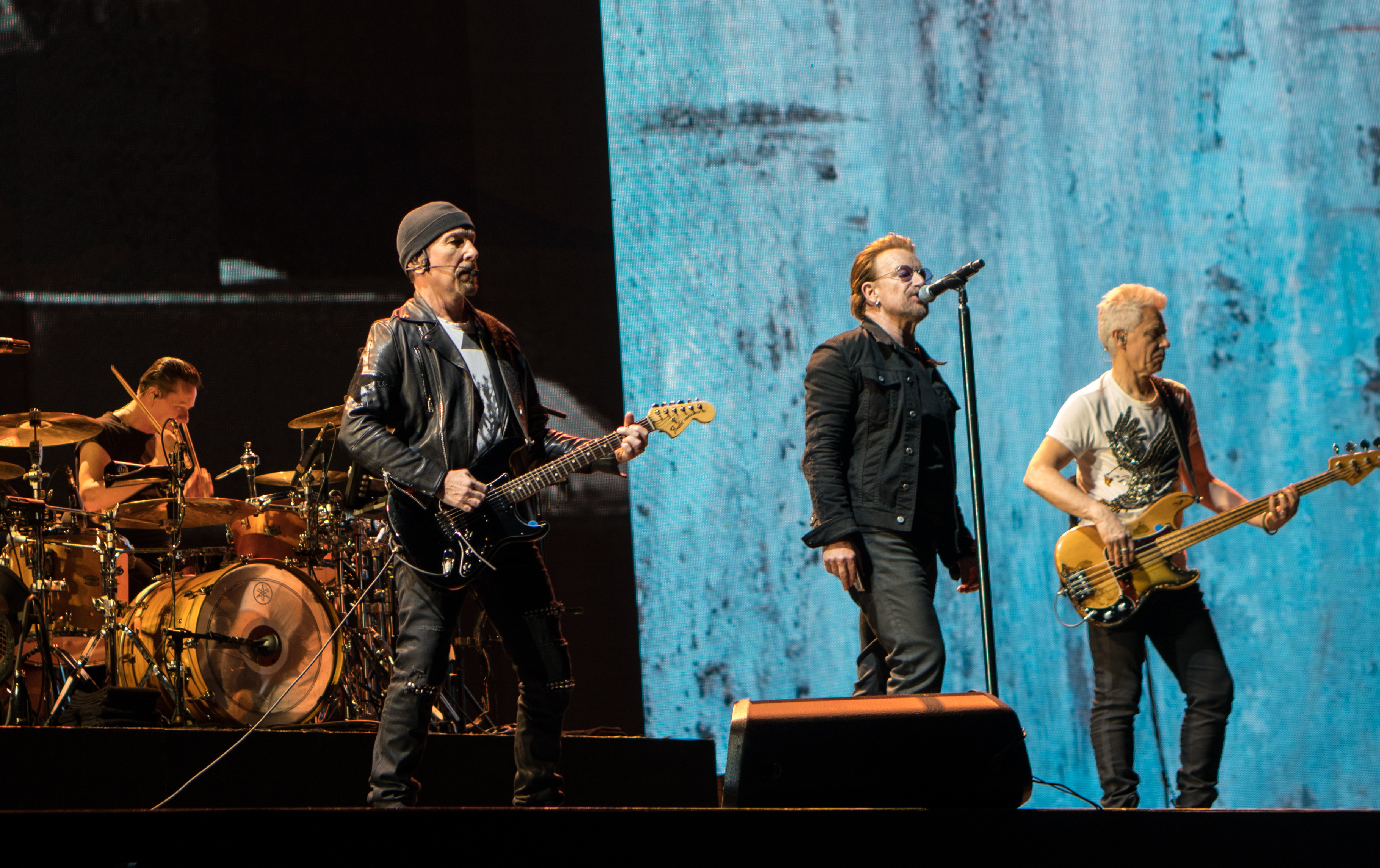

48. U2

For all of the comedic jabs, critical asides, and cultural slights to which U2 is constantly subjected, there is no arguing that they are one of the world’s most successful bands. The numbers don’t lie. But there’s more to it than just success. U2 was, for all of its alleged arrogance and egotism, one of the most consistently earnest and rewarding bands in the world during its prime.

Formed in Dublin in 1976 around Bono (vocals), the Edge (guitar), Larry Mullen (drums), and Adam Clayton (bass), U2 postured itself as part of the punk movement but soon evolved into something else entirely. Its 1980 debut, Boy, combined the band’s overtly political Irish lamentations with an epic, stadium-ready sonic scope. Shot through by the group’s own messianic fixation, it was at once sincere and self-centered, the perfect combination for audiences of the early 1980s.

From the political pointedness of 1983’s War to the proto alt-country majesty of 1987’s The Joshua Tree to the electrofunk undercurrent of 1991’s Achtung Baby, U2 would evolve to become arguably the most important rock band of the next decade. Their stadium-filing tours, airwave-dominating singles, and album-oriented precision made the band a global phenomenon. Ultimately, the elements of punk, new wave, and arena rock that U2 fused together became a sound all their own, and one to which future stadium acts like Pearl Jam, Radiohead, and Coldplay owe an incalculable debt.

Over the course of the 90s, U2 redefined the enormity and spectacle of the live rock show. Playing to ever-larger audiences, the band dedicated its considerable resources to creating an enveloping sonic and visual experience even for crowds numbering in the tens of thousands. As a singer, Bono invoked the arena-scale revivalism of Bruce Springsteen before him, using his tremendous passion and charisma to create intimacy in even the most expansive venues.

All told, U2 has moved roughly 150-170 million records worldwide and are the recipients of a stunning 22 Grammy Awards as well as a 2005 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Photo By:Remy – http://u2start.com/photos/view/26987, CC BY 4.0

47. Santana

Santana is rightly grouped in with other Bay Area acts of the late 1960s, emerging from the same hotbed of creativity, drug experimentation, and liberal politics that spawned the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company and legions of other psychedelic rangers. But Santana was always markedly different, a unit driven by a palpable spirituality and readily distinguished by its propulsive Latin rhythms.

Taking their name from inimitable lead guitarist Carlos Santana, the otherwise constantly shifting unit of players is not only the last band standing from the psychedelic scene, it is also owner of the era’s greatest commercial track record. Santana has dedicated his career to exploring new musical frontiers with divinely-inspired courage while never straying too far from the impulse to please the masses.

Formed in 1967 as a hybrid of Latin soul and the improvisational, acid-driven rock music that was thriving in San Francisco at the time, Santana gained a reputation for its transcendental performances at hotspots like the Avalon and the Fillmore. Their 1969 self-titled debut was met with widespread praise. Representing an absolutely unprecedented sound either in Latin music or in rock, Santana peaked at #4 on the charts, aided by the Top Ten hit “Evil Ways.”

It didn’t hurt that the album came out at exactly the same time that Carlos Santana was melting faces with his career-defining performance as a Woodstock headliner. It was with this classic lineup—Jose Chepito Areas (percussion), David Brown (bass), Gregg Rolie (keys), Mike Carabello (percussion) and Michael Shrieve (drums) — that Santana released two consecutive chart-topping records, the psychedelic milestones Abraxas (1970) and Santana III (1971). Both remain defining records of the era, treading shoulder to shoulder with any of psychedelia’s highwater marks.

Though the original lineup would dissolve at this point, the next decade would find Santana embarking on an ever-deeper spiritual and musical journey with heavy forays into jazz, fusion, and progressive rock. His experimental output during this time resulted in steady critical acclaim and, as could be expected, diminishing album sales. But Santana would prove unkillable, re-emerging in the late 70s, then in the early 80s, and once again with even more stunning commercial results in the late 90s. Every decade would see the guitarist return not just to the stage but to the spotlight.

Santana’s most unexpected success came with 1999’s Supernatural, a musically tepid but commercially potent set of duets between the legendary guitarist and a generation of younger artists like Dave Matthews and Rob Thomas of Matchbox 20. It was the performance with the latter on “Smooth” that propelled the album to 30 million in worldwide sales and assaulted radio listeners with its unbearable 12 week reign at the top of the charts. Indeed, the album also earned Santana the unique distinction of owning the longest gap between #1 records, this being his first since 1971’s Santana III.

Inducted into the Hall of Fame the previous year along with the classic lineup of his band, Santana has little left to prove. Still, he tours and records tirelessly.

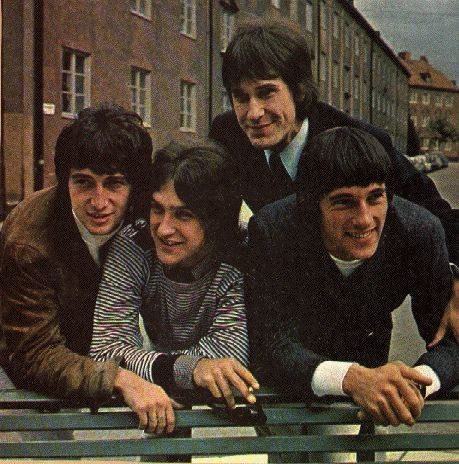

46. The Kinks

The Kinks should have been huge in America. They should stand alongside the Beatles, Stones, and the Who in history’s regard. And yet, they are often seen as 2nd tier British Invaders. Their musical output says otherwise though. Their legacy is, first, a series of riff-heavy, proto-Britpop hits without equal and, second, a sequence of conceptually unified albums that stand among the best full-length players of the era. Formed in North London by brothers Ray and Dave Davies in 1963, the Kinks found success quickly.

With the release of their first single, “You Really Got Me,” in 1964, the Kinks had a #1 hit in England and a Top Ten entry in the US. The charging velocity of their first hit marked a new peak of ferocity from the often-tempered shores of the Thames. The Kinks looked to be well on their way to the same stardom enjoyed by their mates of state. So what went wrong?

In 1965, as the rising Kinks embarked on an international tour, their behavior proved too erratic for their own good. A series of inadvisable missteps began when the band skipped an engagement in Sacramento, intensified when Ray Davies punched a union official for calling the British commies, and peaked when the band skipped out on paying its dues to the American Federation of Television and Recording Artists prior to appearing on a Dick Clark TV special. For these offenses, the latter Federation saw to it that the Kinks were outfitted with a touring ban in America for the subsequent four years.

As their contemporaries exploded into global stardom, the Kinks were locked out of promotion in the world’s biggest rock and roll marketplace. Though this fateful decision would prevent them from attaining the commercial success of their peers, lead singer Ray Davies would retreat to England and consequently compose some of the most rewarding and fully-conceived music of the era. Increasingly, his attention shifted from riff-rockers to character-driven vignettes exploring the boredom, the contradictions, and the simple pleasures of British life. Songs like “A Well Respected Man,” “Waterloo Sunset,” and “Sunny Afternoon” lampooned the conventions and idiosyncrasies of the nation to which the Kinks had become largely bound. Though Brit-centric bent did little to improve their fortunes in America, “Sunny Afternoon” would best even the Beatles for the UK’s top song in 1966.

Subsequent output by the Kinks would focus evermore on exploring the inner-psyche of the modern British man and the identity of the former empire. With Something Else by the Kinks (1967), Village Green Preservation Society (1968), and Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) (1969), Ray Davies revealed an increasingly sophisticated and expansive universe of characters and conceits, every bit as ambitious as the work produced by the band’s more famous friends. With the turn of the decade, the ban on American touring was lifted, allowing the Kinks to promote their next single, “Lola.”

The story of a confused young man and a seductive transvestite became a Top Ten hit on both sides of the Atlantic and ushered in a new phase of American popularity for the Kinks. Unfortunately, the moment also coincided with a dramatic downturn in Ray Davies’ personal fortunes. Separation from his wife led to deep depression and an overdose on antidepressants. By the time of his return in the early 70s, the band had shifted headlong into a series of more theatrically-driven records that were neither as critically nor as commercially rewarding as the band’s best work. In spite of yielding another Top Ten American hit with the calypso-inflected “Come Dancing” in 1983, the glory days were largely in the rearview for the Kinks.

Though a number of studio records and solo projects would follow in the next decade, the Kinks’ greater impact at that point was readily apparent in the mid-90s Britpop boom. The Kinks called it quits in 1996, even as bands like Oasis and Blur acknowledged their heavy musical debt to the Davies brothers from the top of the charts. The Kinks never achieved the kind of success they should have in the US, but they have a permanent place in Cleveland thanks to their 1990 enshrinement in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

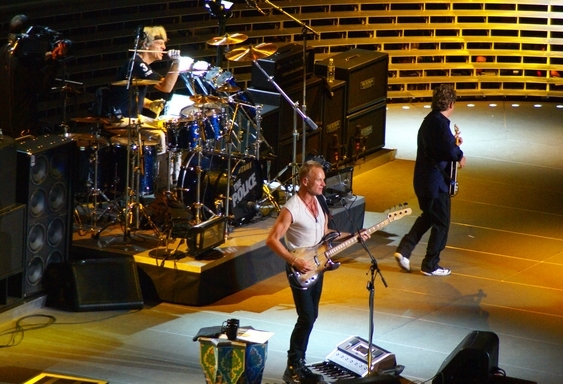

45. The Police

These guys can’t stand each other. I mean, they really can’t be in a room together, let alone on tour. Don’t let this discourage you from listening to them though. Across six years and five albums, the Police made scarcely a mistake. All evidence suggests that they were a bunch of miserable egomaniacs but you don’t have to hang out with them to get into their catalog.

Formed in 1977, the trio of Sting (nee Gordon Sumner) on bass, Henri Padovani on guitar and Stewart Copeland on drums wasn’t exactly a punk band but they shoehorned perfectly into a year distinguished for a flood of new snot-nosed icons. They quickly separated themselves from their ideologically rigid contemporaries by bleaching their hair and taping an ad for Wrigley’s chewing gum. Though the ad brought the struggling band some much needed cash, it was never aired. And don’t bother looking for it (I tried really hard). Even The Police can’t find it.

But chewing gum was small potatoes. Copeland founded the I.R.S. label with his brother Miles. In addition to itself becoming one of the foremost new wave labels of the early 80s, (holding a stable that included R.E.M., the Go-Go’s and the Fine Young Cannibals) I.R.S. released the debut single, “Fall Out” by The Police. Shortly thereafter, Padovani was replaced by Andy Summers, cementing the lineup that would eventually land in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Miles Copeland financed their first record but when he heard them rehearsing “Roxanne,” he shopped the single to A&M and scored them a deal. The single was released to little attention before the album was even completed. With their 1978 debut, Outlandos d’Amour (1978), the Police would showcase a tight, tense and wiry sound, as punky as anything they’d ever produce.

Though radio programmers in the UK avoided lead single “Roxanne” (at first) for its risqué subject matter, Americans were decidedly more comfortable with hookers in their Top 40. The single propelled The Police into a reputation-building North American van tour.

As British New Wave began pouring into the US Billboard charts, the Police capitalized with 1978’s, Reggatta de Blanc. Taking aim at the charts, the Police landed with moody hits “Walking on the Moon” and “Message in a Bottle.” They followed with three consecutive records of relative perfection and total commercial appeal, with Zenyatta Mondatta (1980), Ghost in the Machine (1981), and Synchronicity (1983) gradually making the Police one of the biggest bands in the world.

Synchronicity, in particular, is the rare case where you can hear a band succeeding and crumbling all at once. Just as the Police were achieving new world-conquering heights of fame on the strength of their lead singer’s growing stardom, it was also becoming increasingly apparent that no band could contain the mighty Sting. Synchronicity gave The Police no fewer than five charting hits, including their first #1, the gorgeous stalker-meets-girl ballad, “Every Breath You Take.” “Every Breath” beat out Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” for Grammy’s Song of the Year.

The Police took a hiatus following the success of Synchronicity, during which time Sting released his first solo album, The Dream of the Blue Turtles (1985). The night before the band reconvened to record its sixth studio album, Copeland fell off a horse and broke his collarbone. Apparently, he and Sting consequently entered into an irreconcilable dispute over the right drum machine to use. Lacking resolution, they called it quits in 1986. All told, the Police moved about 75 million records worldwide.

They joined the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003 and went on a reunion tour in 2007 during which, predictably, they found it unbearable to be around one another.

Photo By: Lionel Urman, CC BY-SA 3.0

44. Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band

If you’ve ever been to a Bruce Springsteen show, then you know it’s a lot like an old-timey tent-revival. The Boss performs like a preacher possessed by the spirit of rock and roll, often stretching his performances into exultant four-hour engagements. There’s only one band in the world with the muscle, the versatility, and the sheer stamina to support Springsteen’s excessive musical generosity. Historically relegated to the collective role of sidemen and generally overshadowed by Bruce’s massive star, individual members of the E Street Band would, over time, be increasingly recognized for their individual and shared contributions to one of rock’s most important catalogs.

Most of the band’s founding members had played with Bruce in any number of his early ensembles before coming together to record Springsteen’s debut. 1973’s Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ featured Danny Federici (keys, accordion), Garry Tallent (bass), Vini Lopez (drums), David Sancious (keys), and of course, the Big Man, Clarence Clemons, on saxophone. Following their debut, the collective adopted its name from the E Street house (owned by Sancious’s mother) where the band made its first practice space.

The name would be the keyboard player’s one lasting contribution to the group as he soon departed to form his own jazz fusion band. Sancious was replaced by Roy Bittan. Around the same time, the departing Vini Lopez was replaced by the Mighty Max Weinberg. By the end of 1974, Springsteen had added the fiery Steven Van Zandt on guitar, cementing a band capable of enormous power and sensitivity. Over the next decade, the lineup provided Springsteen with a force of reckoning. Clemons’ full-throated sax, in particular, gave Bruce a massive musical foil and a signature sound.

On monster records like Born to Run (1975), The River (1980), and Born in the U.S.A. (1984), the E Street Band powered a factory of mega-hits, including classic rock staples “Thunder Road,” “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out,” and “Glory Days.” By the middle of the decade, Springsteen was the biggest star in the world and E Street was the only band big enough (in sound and number) to support him.

Springsteen has opted, on occasion, to tour and record without his backing band. Neither decision is ever met with much excitement from fans (excepting the fairly awesome Seeger Sessions Band). However, the occasional respite from touring has given his bandmates the opportunity to pursue fame in their own right.

Throughout the 90s, drummer Max Weinberg beamed into millions of television sets a night as the bandleader for Late Night With Conan O’Brien. Stevie Van Zandt would gain fame for his supporting turn as Silvio Dante on HBO’s The Sopranos, holding the rare distinction of living through all eight of the show’s bloody seasons.

Members of the band have also provided session and touring support to an incredible list of legends including Bob Dylan, the Stones, David Bowie, the Grateful Dead and Sir Paul McCartney. The deaths of Danny Federici in 2008 and the irreplaceable Clarence Clemons in 2011 have left gaping vacancies on E Street. But in 2014, after four decades in service to Springsteen’s mission, these perennial sidemen were awarded their own placard in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

43. Buddy Holly & the Crickets

When you think about the enormous shadow that Buddy Holly casts over all of rock and roll history, it boggles the mind to think that his entire body of work was produced in just two years. As well known in history for his untimely death as for his unique hybrid of rockabilly swagger and pop songcraft, Buddy Holly is one of the most frequently name-checked influences of the Golden Age.

As a teenager, Buddy Holly was primarily interested in the country and blues music that surrounded him in his native Lubbock, Texas. He formed various combos with friends that included Sonny Curtis and Jerry Alison, eventually securing a series of opening dates for a young Elvis Presley in 1955. This stint led Holly full-throttle into rock and roll. By the time he landed a contract with Brunswick Recordings, Buddy Holly had cemented his backing group with Allison on drums and Larry Welborn on bass.

It was this combo that recorded “That’ll Be the Day” as the Crickets, a single that would go on to sell a million copies and top the Pop, R&B, and UK charts. Not only would this become an oft-covered rock and roll standard, but it would also produce a new kind of rock and roll artist. Where Elvis Presley was recasting and interpreting a melange of blues, country, and hillbilly music, Buddy Holly was spinning these elements into his own original compositions. His role as one of the first rock and roll songwriters would provide the Crickets with a stream of charting hits, highlighted by radio staples like “Not Fade Away,” “Words of Love,” and “Peggy Sue,” most assuredly one of pop history’s most beloved muses.

Sadly, Buddy Holly would not live to see just how far and wide his influence would ultimately be felt. As the Crickets rocketed to fame, a dispute with his manager led Holly to embark on a solo tour of the Midwest as part of a traveling rock and roll package. The Crickets added childhood friend Sonny Curtis to fill in for local performances and eagerly awaited the return of their leader. Holly’s tour was marked by hardship, particularly as a consequence of subzero temperatures and a broken-down tour bus with a shoddy heating unit.

These conditions prompted Holly to charter a flight from Clear Lake, Iowa to Moorhead, Minnesota. He was joined by rising tejano star Ritchie Valens and radio/recording personality The Big Bopper. All were killed, along with the pilot, when the airplane disappeared off the radar moments are takeoff. The deaths, famously rhapsodized in singer-songwriter Don McLean’s 1972 hit “American Pie,” came to be referred to as the Day the Music Died.

Still, even in his death, Holly would achieve a lasting impact, felt not least of all in the music of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the legions of others inspired thusly. Indeed, it is often said that the Beatles selected their entomological name in tribute to the Crickets. As for said Crickets, they would actually subsist in relative perpetuity in spite of Holly’s demise. Sonny Curtis would become the group’s de facto and nearly perennial leader. Incredibly, Jerry Allison and Curtis, both in their 80s, remain affiliated with the Crickets today.

They, along with additional long-time members Joe. B. Mauldin and Niki Sullivan, joined Holly as part of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s inaugural 1986 class.

42. Smokey Robinson & The Miracles

With his sophisticated singing, his debonair image, and his authorship of some of the greatest hooks human ears have ever beheld, Smokey Robinson played a critical role in earning Motown its title as Hitsville. A native of the Detroit that he hoped to put on the musical map, Smokey Robinson partnered with childhood friends Pete Moore and Ronnie White in 1955 to form the Five Chimes. This would be the first incarnation of the future Miracles, so-named in 1958 with the addition of Claudette Robinson, Bobby Rogers, and Marv Tauplin.

A chance meeting with aspiring songwriter Berry Gordy in 1957 would help Robinson secure his first few single releases. The Miracles released “Shop Around” through Gordy’s new label, Motown. The Miracles and Motown quickly earned their first million seller.

Smokey Robinson and the Miracles proceeded to soundtrack the coming decade, scoring a total of 26 top 40 hits, including unimpeachable pop gems like “You’ve Really Got a Hold On Me,” “I Second That Emotion,” “The Tracks of My Tears,” and the “Tears of a Clown.” Smokey’s songwriting genius was not merely reserved for his own work though. As one of Motown’s most prolific pens, he also authored mega-hits for Mary Wells (“My Guy”), The Marvelettes (“Don’t Mess With Bill,”) and, most importantly, The Temptations (“Get Ready,” “My Girl,” “The Way You Do the Things You Do”).

In addition to sustained chart success as a solo act throughout the 70s, Smokey also served as Motown’s vice president for a period and maintained his association with the groundbreaking company until its sale in the early 1990s. Following Smokey’s departure in 1972, various incarnations of the Miracles have been revived for tours of duty on the oldies circuit, including some permutation of original members and mercenary Miracles. Today, Smokey Robinson is a twice-enshrined member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, both as a solo artist and as the leader of the Miracles.

41. The Faces

The genealogy of the British Blues Rock scene is remarkably incestuous. So well-acquainted are its various members with one another that you might be inclined to picture England as one big cluster of pubs. The Faces do nothing to dispel this impression given the high profile affiliations of its personnel and the shambolic booziness of its best recordings. The Faces formed in 1969 from the ashes of two groups.

Now stick with me here because, as I warned you, it gets a little complicated. After enjoying commercial success and suffering at the hands of record company indiscretion, lead singer Steve Marriott departed Brit-soul pioneers the Small Faces in order to join Peter Frampton in Humble Pie. At about the same time, singer Rod Stewart and guitarist Ronnie Wood exited the Jeff Beck Group. Just to complicate matters, Jimmy Page had recently disbanded the Yardbirds and was poking around Stewart’s scene in search of a singer for the as-yet unnamed Led Zeppelin.

Ultimately, Stewart and Wood joined erstwhile Small Faces Ronnie Lane (bass), Kenney Jones (drums) and Ian McLagan (keys). They dropped the “Small” and one of the great boogie bands was born. So too was Rod Stewart’s ticket to superstardom stamped. The Faces offered a muscular, chugging backbone to Stewart’s inimitable rasp. Between 1970 and 1973, the Faces released four records, with 1971’s A Nod Is As Good As A Wink …To a Blind Horse standing as the group’s peak artistic and commercial accomplishment. The album topped out at #6 in the US and #2 in the UK, eventually going Gold on the strength of the elementally perfect rocker “Stay With Me.”

In spite of Wood’s unmistakable riffing and McLagan’s ebullient barrelhouse playing, “Stay With Me,” and increasingly, the band’s live shows, appeared as little more than opportunities to showcase the ever-more popular Stewart. Through extensive touring in the US and UK, Stewart gradually made the transformation from Rod the Mod to the far less humble Rod the Bod.

As Rod Stewart turned his attention increasingly to his solo work, his fellow Faces grew ever more disillusioned. Indeed, under Lane’s leadership, the Faces would record Ooh La La (1973) largely without Stewart present in the studio. In spite of a fine (and rare) vocal by Wood on the well-loved title track, Stewart publicly criticized the album. Lane departed in anger and the Faces petered out over two subsequent years of uninspired touring.

Ronnie Wood went on to join the Rolling Stones in 1975. Kenney Jones would temporarily replace the deceased Keith Moon in a 1980s incarnation of The Who. Sadly, Lane’s solo career would be cut short by a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, a condition which claimed his life in 1997. McLagan passed away in 2014. Rod Stewart would, of course, go on to become one of the most successful rock singers in history. His output was so excellent throughout much of the 1970s that he can almost be forgiven for the dreck that marks his latter (30) years.

The Faces are Hall of Fame inductees, as is Stewart as a solo musician. And the fact that you can get from the Faces to pretty much any other major act from their time and place in three people or less basically makes them the Kevin Bacon of British rock music.

Photo By: Egghead06 at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

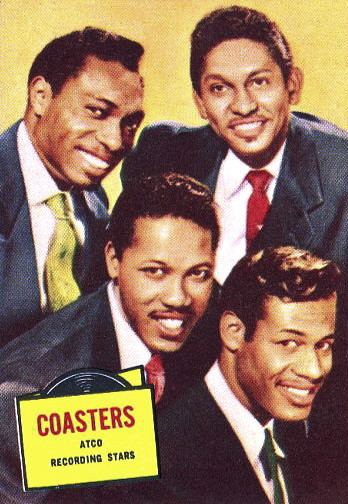

40. The Coasters

Groups like the Coasters prove that sometimes it’s the idea and execution of a band that matter more than the individual members. To the point, several dozen individuals have toured at various points under the name, which explains how a group that was formed in 1955 remains a viable oldies circuit act even today. That said, its very best lineup would be responsible for some of the rock and roll era’s most engaging, enduring, and beloved hits.

Formed as a spin-off of rock and roll doo-woppers The Robins in Los Angeles, The Coasters became the primary vehicle for the output of famed songwriting duo Leiber & Stoller. The lineup of Carl Gardner, Billy Guy, Cornell Gunter and Will “Dub” Jones relocated to New York to record on Atlantic with their songwriting braintrust in 1957. The partnership touched off a string of hits delivered with affable, upbeat, and frequently humorous performances. Between ’57 and ’59, and with the support of saxophonist King Curtis, the Coasters rolled through the charts with good-natured perennials like “Young Blood,” “Searchin’,” “Charlie Brown,” “Poison Ivy,” and, with “Yakety Yak” their only pop #1.

With the help of their ace songsmiths, the Coasters became one of the first, most prominent, and most successful acts to cross over from the R&B charts to the Billboard mainstream. In 1987, they would be rewarded for their efforts by becoming the first group (as opposed to a guy and his backing band, such as Buddy Holly and the Crickets) to gain induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The band’s fortunes declined sharply with the end of the rock and roll era, and several of its members met ignoble and violent deaths. The last remaining original member, Carl Gardner passed away in 2011. His son, Carl Jr. tours as the leader of the only currently authorized incarnation of The Coasters.

Photo By: TGC-Topps Gum Cards-photo from ATCO Records – eBay itemfrontback, Public Domain

39. Red Hot Chili Peppers

L.A.’s foremost purveyors of a punk-funk-hip-hop hybrid that prefigures much of the genre-bending of the later alternative era, the Chili Peppers performed their first shows in 1983 as Tony Flow and the Majestic Masters of Mayhem. The name was, fortunately, short-lived. The band, by contrast, would brave countless lineup changes to remain a going, relevant, and even increasingly lucrative concern for the next 40 years.

The band originally formed around high school friends Anthony Keidis, Michael “Flea” Balzary, Hillel Slovak, and Jack Irons. Though it would take the Chili Peppers almost a decade to become the rock radio juggernaut we know today, opportunity actually came remarkably fast for the musically-literate hooligans. They scored a 7-album deal with EMI less than a year from formation.

They released their self-titled debut in 1984. Unfortunately, studio tension between the band and its producer resulted in a slick, heavy-metal production style not befitting of the band’s quirk and versatility. Fortunately, they found a kindred soul in the producer of their artistic breakthrough.

For their second record, Freaky Styley (1985), the Chili Peppers enlisted Funkmaster General George Clinton to produce. Clinton was the second-biggest influence on the album, the first being heroin. Slovak and Keidis in particular began to develop drug habits that would do nothing less than define the band’s future history. In 1988, immediately following the supporting tour for their third release, 1987’s Uplift Mofo Party Plan, Hillel Slovak overdosed. Jack Irons left the band to grieve (building a brilliant resume by resurfacing several years later behind the kit for Pearl Jam). Flea and Keidis were left to struggle with their own addictions.

They resolved to push forward however, adding John Frusicante on guitar and Chad Smith on drums. It was with this lineup, and the record Mother’s Milk (1989), that the band would glimpse greater success. Indeed, the band’s slap-bass assault on Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground” caught the attention of the majors. The subsequent bidding war ended with the Chili Peppers signed to Warner Brothers and paired with producer Rick Rubin.

Rubin rented out Harry Houdini’s haunted mansion (which he now owns) and sequestered the band there (except for Smith, who is genuinely afraid of ghosts). As usually happens when Rick Rubin sequesters a band in a haunted mansion, they came out on the other side with an out-and-out, bonafide masterpiece. Everything the band had been to that point converged on the dizzyingly eclectic and sprawling Blood Sugar Sex Magic (1991). The album’s 13 million in sales were largely fueled by the heroin-inspired “Under the Bridge,” possibly alternative music’s first power ballad. It would also be a blueprint for the band’s future commercial success and increasing preoccupation with hooky melodicism. A landmark in its time (and a fertile time at that), it still sounds urgent, relevant, and innovative today, perhaps even moreso.

On future records like Californication and Stadium Arcadium, the Chili Peppers would come to lean more heavily on melodic songcraft than on the rap-funk hybrid that delivered them to success, ultimately becoming an unstoppable hit-making enterprise and, in 2012, owners of a placard in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

38. Sex Pistols

The Sex Pistols are the definitive punk band, as much for their anarchic music as for the fact that they made it and blew it about as hard as anybody before or since. It’s hard to think of a band that changed more in music or popular culture while leaving a smaller body of work. All told, the Sex Pistols released one full-length LP and four singles during slightly over two years of existence. They also managed to plow through their relationships with no fewer than three record labels in that space of time, embarking on tours marked by violence, rioting, cancellations, and arrests. Their nihilist antics, their devolutionary ambitions, and their profanity-laced disdain for all of society’s totems made them public enemy #1 during their brief reign. All of these qualities also made them a game-changing force in music history.

Formed in 1975 around Steve Jones (guitar), Paul Cook (drums), and Glen Matlock (bass) as part of the London Pub Rock scene, the group found its identity with the addition of snotty, loud-mouthed singer Johnny Rotten. Their reputation would be galvanized by a partnership with manager Malcolm McLaren, fresh off of a brief and unfruitful stint handling the New York Dolls in the US. When they self-destructed, McLaren absconded back to England with the Dolls’ image, and that of Television’s Richard Hell, using their ideas to open a clothing boutique called SEX.

McLaren’s shop, and his influence, were considerable in crafting the Sex Pistols. Though Rotten’s safety-pinned attire and green hair were of his own design, McLaren would have an active hand in imbuing the singer with his radical left wing politics (which have long since been supplanted by his declared identification with Trumpism in the 2010s).

In spite of its reputation for being more attitude than talent, the Sex Pistols would also quickly gel into a musically tight and ferocious unit, proving a powerful outlet for explosive blasts of well-articulated political subversion. As the Sex Pistols merged a set of savage rock and roll covers with original tunes attacking British royalty, consumerism, and conservative politics, they attracted a growing following of future punk leaders like Siouxsie Sioux and Billy Idol. They also succeeded in landing a deal with EMI, where they recorded their debut single “Anarchy for the UK” in late 1976.

Early the following year, the Sex Pistols embarked on a 20-date tour but obstruction from local governments caused the cancellation of all but seven engagements. Trouble continued for the Pistols as EMI employees, disgusted by the band’s message, refused to ship its single. Their behavior during the tour was also covered substantially by the press, which developed a morbid fascination with the band’s proclivity for spitting, fighting, vomiting, and bleeding both in concert and while socializing. Cameras swallowed up Rotten’s outrageously insolent hostility toward all things revered in British culture.

To the point, the Pistols ousted their own bassist, Glen Matlock, for his professed love of the Beatles. He was replaced by Sid Vicious, who had almost no idea how to play the instrument but who had the right look and general disregard for humanity. Shortly thereafter, the Pistols were also ousted. Under intense internal pressure by British government officials, EMI bailed on their contract with the Pistols. The band promptly celebrated a new contract with A&M by storming the label’s offices, terrorizing employees, destroying bathrooms, and bleeding in the hallways.

Though they had already recorded and pressed their next single, “God Save the Queen,” A&M dropped the band and destroyed the run of records. The Pistols signed with Virgin two months later and, in spite of protest from packing employees, managed to ship “God Save the Queen.” Its subversive lyrics decried the Queen, resonating with countless young working class Britons disillusioned by the deeply classicist implications of the crown. It was thus that, in spite of having been banned from radio play pretty much everywhere in England, “God Save the Queen” reached the second spot on the sales charts. It was held from the top, according to most accounts, by government intervention.

Virgin released the Pistols’ one and only record, 1977’s punk bible, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols. The album was a #1 hit and only further magnified the group’s penchant for chaos. In particular, Sid Vicious proved an asset insofar as the press was concerned. Every event saw him in a fight or a confrontation, most of them instigated by Vicious himself. The band also found itself the target of violence and attacks as its leftist politics inflamed conservative Britons.

Seeking to capitalize on their instigative tendencies, Malcolm McLaren booked the band for a US tour largely confined to southern venues frequented by rednecks. He hoped to grab more headlines and was rewarded with constant violence, most often involving an absolutely unrepentant and heroin-addicted Sid Vicious. It was during this 1978 tour that Rotten, fed up with Sid’s antics, and feeling increasingly alienated from Jones, Cook, and McLaren, disbanded the Sex Pistols one song into their final US gig.

Assuming his Christian name, John Lydon, he became frontman for the critically acclaimed post-punk group Public Image Ltd. Sid Vicious overdosed on heroin while awaiting trial for the murder of his also-heroin-addicted groupie girlfriend Nancy Spungen. The Sex Pistols were characteristically scabrous when inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which they called a “piss stain.” However, the original members, all still living, have since reunited on several occasions for extremely lucrative reunion tours.

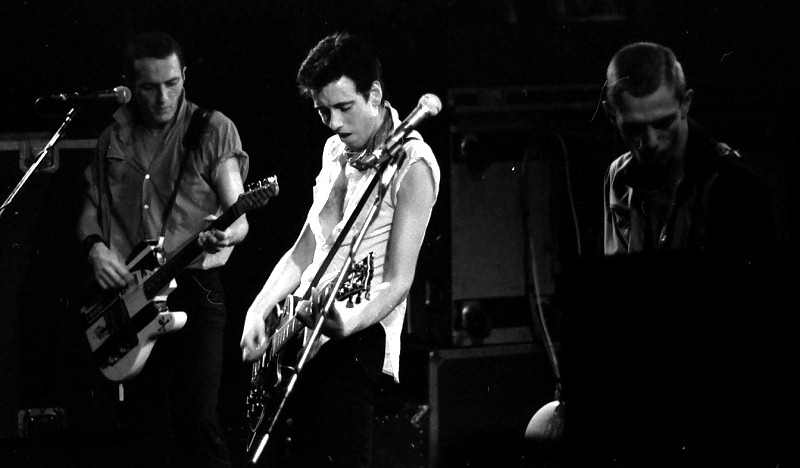

37. The Clash

The Clash were close compatriots with the Sex Pistols and, to be certain, their initial success came as they were swept up in the orbit of their far more self-destructive mates. However, quite unlike the one-dimensional and imploding Pistols, The Clash were sharply focused, musically versatile, and even commercially viable. Whether these qualities made them something less than authentic from the perspective of the punk community is a matter which has been much-debated since the Clash rocketed to stardom in the late 1970s. What is not much worth debating is the impact of their music, which has been unarguably huge and ongoing.

Like many early British punkers, the Clash cut their teeth as part of the British Pub Rock scene. Here, working class bands like the 101ers (featuring Joe Strummer) and the London SS (featuring Mick Jones) offered back-to-basics working class rock heavily influenced by early American blues, R&B, and R&R. This all changed with the emergence of New York’s punk scene and, most particularly, the Ramones. The young acolytes of the pub rock scene viewed the rising punk movement as an outlet for their own frustrations.

First came the Sex Pistols. When Mick Jones and Joe Strummer, separately but both present, witnessed the first live performance by the Sex Pistols, each immediately aspired to change musical directions. Through various shared acquaintances, they would ultimately join forces with Paul Simonen (bass) and Terry Chimes (drums) to form the Clash. They opened for the Sex Pistols after only a month of practice. The embarrassing performance inclined them to retreat into several months of intensive rehearsal, the results of which are readily audible on their classic 1977 self-titled debut. Though like the Sex Pistols much of their political invective came about through managerial coaxing, their revolutionary posturing was more than convincing on immediate genre classics like “White Riot” and “I’m So Bored With the USA.”

Among the pack of notoriously snotty British punks, the Clash seemed somehow to be the most sincere and empathetic. Their discontent was relatable. So too was their musical vision more expansive than that of most three-cord antagonists, as demonstrated by the Junior Murvin cover, “Police and Thieves.” This recording would arguably touch off the free-flowing interchange between punk and reggae that manifested in future bands like The Specials, the Police, and Sublime.

With the success of their debut, the Clash upgraded drummers, replacing Chimes with Topper Headon and assuming their classic lineup. It would be their third record, an unlikely punk double LP entitled London Calling, that would assure their status. With the Sex Pistols already two years dead, the Clash produced what is certainly the most musically eclectic and accomplished work of the original punk era. Released at the end of 1979 in the UK and the start of 1980 in the US, London Calling was a charting success on both continents. Unlisted final track “Train In Vain” made the US Top 40 and spurred a supporting tour in which the Clash took on and justified their identity as “the only band that matters.”

Detractors criticized the band’s increasingly commercial sound but the album’s mix of rockabilly, reggae, ska, and rock and roll underscored punk music’s most inventive possibilities. As the bands around them descended into heroin abuse and nonexistence, the generally clean-living Clash entered the 1980s determined to make good on their commercial breakthrough. They faltered somewhat on the quixotically enormous three LP sprawler Sandinista! (1980), which featured an even wider breadth of stylistic endeavors. In 1982, though, the Clash rebounded in a big way with the New Wave inflected Combat Rock. “Should I Stay Or Should I Go” and “Rock the Casbah” were both huge hits.

But they would be the last for the Clash. Headon was the first to go, fired for his excessive heroin abuse. Though they would continue to tour and book sessions for a follow-up record with a rotating cast of drummers, five years of touring and recording had left the band bedraggled and dispirited. A powerful force for much of its run, the Clash quietly disbanded in 1986 but its former members frequently collaborated on solo projects. Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2003, the Clash rise well-above the sophomoric claim of having sold out by leaving behind an inimitable and endlessly relevant body of work.

Photo By: Helge Øverås – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

36. R.E.M.

Who would ever have guessed that this band would go so quietly into retirement. When they disbanded in 2011, it was the end of a 31 year run that saw some of the quirkiest and most genre-defining work of both the New Wave and alternative eras. They were also responsible for a catalog of rare emotional depth, variety, and popcraft. When R.E.M. called it a day, they left behind them a body of work rich with rewarding long players and indelible singles. Even if you can’t understand just what the hell lead singer Michael Stipe is saying at least 40% of the time, their Southern gothic jangle and their lyrical mystique would drive the definitive alternative band to massive mainstream success.

R.E.M. formed in 1980 and incubated their sound in the collegiate cauldron of Athens, Georgia. First as critical favorites just a touch outside of the mainstream and eventually as elder statesmen during the alterna-boom, R.E.M. defied the disposable nature of the New Wave era to become one of the biggest bands in the world.

Releasing their debut, Murmur, in 1983, R.E.M. achieved its first glimpse of college radio fame with “Radio Free Europe,” earning praise from critics and gathering a small regional audience in its fertile Athens, Georgia scene. Though the next several albums would build on the band’s strong support on campuses and in the music press, R.E.M.’s true commercial breakthrough came with Document (1987). Muscular, riff-laden and snare-heavy power pop with a Reagan-era political conscience, Document contains the first batch of R.E.M. songs to achieve household familiarity, particularly “The One I Love” and “It’s the End of the World As We Know It.”

With Out of Time (1991), its second major label release, R.E.M. would have its first US #1 album and a quadruple platinum certification. The lushly orchestrated set saw the band at once stepping up its production ambitions and its sightline on the charts. “Losing My Religion” ascended with help from a video oozing with 90s weirdness, not to mention from the broader ‘modern rock’ explosion. Suddenly, R.E.M.’s odd collision of cryptic imagery and aching Southern regret was exactly what radio programmers were looking for. Ten years on, the band was entering its second classic phase.

The next three records, Automatic for the People (1992), Monster (1994), and New Adventures in Hi-Fi, witnessed the group truly capitalizing on its status as the cream of the alternative crop. With “Man on the Moon,” “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?,” and “Electrolite,” R.E.M. became well-acquainted with the upper reaches of the Modern Rock charts.

Unfortunately, the group also endured a set of mid-90s tours beset by health problems and injuries, leading to the departure of drummer Bill Berry in 1997. Though the band replaced him with a drum machine and produced several more generally enjoyable but tepidly received records, they called it quits four years after their 2007 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Today, these so-called “alternative” rockers are responsible for the sale of a decidedly not-alternative 85 million records.

35. Run D.M.C.

There is no group deserving of more credit for helping hip hop move from the city streets to suburban households than RUN D.M.C. Marking the point of transition from Old School to New School and setting the course for hip hop’s sound and fashion in the 1980s, Run D.M.C. helped define rap while demonstrating its theretofore unseen commercial power.

Joseph Simmons, Darryl McDaniels and Jam Master Jay grew up together in the Hollis neighborhood of Queens and first began performing as a unit in 1981. As the younger brother of future Def Jam honcho Russell, Joseph Simmons was well-connected from the start. Some of his earliest performances were as the DJ for Old School hero Kurtis Blow. But it wasn’t until the aspiring rappers had completed high school and enrolled in college that Russell was willing to help his younger brother’s group produce their debut single.

“It’s Like That/Sucker MCs” launched Run D.M.C. in 1983, reaching #15 on the R&B charts and securing the trio a growing underground following. Their self-titled debut, the following year, unveiled the group’s guiding formula. Sampling hard-rock guitar riffs and merging them with the tough, lean vamps that would become Def Jam’s trademark, tunes like “Rock Box” gained immediate attention. So too did their Adidas sneakers and leather jackets, a far tougher image than the glammy post-disco proclivities of Grandmaster Flash and other Old Schoolers.

In both their street attire and the harder edge of their music, Run D.M.C. had initiated the graduation to New School. Legions followed in their wake, with artists like the Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, and L.L. Cool J also matriculating. By 1985, Run D.M.C. had achieved substantial cultural importance, with its “Rock Box” becoming the very first rap song ever to play on MTV.

The next year, teaming with Rick Rubin, Run D.M.C. produced Raising Hell, a triple platinum release that convinced all who doubted it to this point that hip hop was a potent commercial force. Driven by a critically vaunted cover of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way,” and a video collaboration with the classic rockers, Run D.M.C. tallied a list of first-time accomplishments for its genre.

“Walk This Way” became the first rap song to make the Billboard Top 5, peaking at #4, and the album became the very first rap record to top the R&B charts. Critics then and today regard this as one of hip hop’s milestone recording events, arguably the launchpad for the genre’s Golden Age. Their 1987 support tour alongside the Beastie Boys was similarly instrumental in the genre’s history.

As the decade wore on, and particularly as commercial attention turned toward New Jack Swing and West Coast G-Funk in the early 90s, Run D.M.C.’s relevance began to fade. Personal problems contributed to the group’s decline through the rest of the decade, leading Jam Master Jay to pursue outside projects such as an ultra-successful collaboration with Onyx on 1993’s nasty smash hit, “Slam.”

Though Run D.M.C. continued to enjoy high regard, it was now as elder statesmen. By the end of the decade, the trio called it quits. Jam Master Jay’s shocking shooting death in 2002 ended any chance of a true reunion, though in 2009, Run D.M.C. became only the second hip hop group, after Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

34. The Byrds

The Byrds were conspicuously at the forefront of rock music in its most fertile decade, most particularly within their home state of California, which itself seemed largely to stand on the forefront of American popular music in the 1960s. As folk music morphed into psychedelic music, and as psychedelic music subsequently turned to country rock, and even as country rock gradually mellowed into the singer/songwriter era, the Byrds were catalysts.

The lineup for this Los Angeles-based group would change endlessly during its decade of existence with only founding guitarist Roger McGuinn remaining as a constant throughout. Forming a folk trio in 1964 with David Crosby and Gene Clark, McGuinn would be profoundly changed by his exposure to the Beatles. As the band began to actively pursue a blend of folk harmonies and rock sensibilities, they added Michael Clarke on drums and Chris Hillman on bass.

Together, they forged an utterly new invention called folk-rock. Grounded by McGuinn’s jangling 12-string guitar, they earned praise from Bob Dylan himself for their cover of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and, reaching #1 in both the US and the UK, the song touched off the folk-rock boom and served as its template.

In 1965, the Byrds once again returned to the top spot in the US for their take on Pete Seeger’s folk bible-verse standard, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” Ironically, given the prehistoric origins of its lyrics, it would become among the most urgently emblematic songs of an increasingly tumultuous decade.

Immediately thereafter, and once again, the Byrds helped to spearhead the decade’s next musical expedition, this time with the prescient Fifth Dimension (1965) and its stoney, raga-inflected, “Eight Miles High.” In many ways, the song’s success was actually fueled by a broadcasting ban invoked by its presumed drug references.

Given the success the Byrds had already achieved as leaders of the folk-rock movement, their association with psychedelic music made them one of the most visible exponents of an otherwise underground form. Over two subsequent albums, however, the Byrds had already begun to move on. Adding the troubled but brilliant Gram Parsons to their lineup, the Byrds were increasingly incorporating pedal steel and other country instrumentation into their work. In 1968, even as flower power was in full bloom, the Byrds released Sweetheart of the Rodeo, as straightforward a country album as any rock band had yet produced.

Its traditionalism was a quiet revolution. Even before the great psychedelic burnout sent the surviving hippies out to the country in search of cleaner living, the Byrds produced this harmonic blend of countrypolitan Nashville, backwoods Appalachia, and sunny southern California. Though not a commercial or critical success upon immediate release, it is today largely considered among the most influential records in rock history, spurring the move toward the increasingly laid-back country-rock sound that would dominate FM radio in the 70s.

By the end of the decade, the Byrds were splintering. Crosby had departed for supergroup fame and Gene Clark left the band because his fear of flying prevented him from touring. And in spite of his influence on the musical direction of the band, Gram Parsons’ substance abuse issues and a power struggle with McGuinn led to his ouster even before the release of Sweetheart. So burnt out were the Byrds that they foolishly rejected a 1969 invitation to play Woodstock.

The Byrds largely petered out before splitting for good in 1973. Parsons would enjoy critical acclaim both solo and, alongside Chris Hillman, with the Flying Burrito Brothers, before succumbing to an overdose at age 26 in 1973. Following his departure, David Crosby began his lifelong role as “C” alongside “S” and “N.” Today, Byrds reunions are infrequent and legal acrimony has persisted between surviving members but the impact made by these Rock and Roll Hall of Famers remains enormous, with bands like R.E.M., Big Star, and Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers citing them as a chief influence.

33. Parliament/Funkadelic

If there was such a thing as Mt. Funkmore (and God willing, one day there will be) James Brown would be George Washington and George Clinton would be Abraham Lincoln. I’ll leave it to you, dear reader, to speculate about Jefferson and Roosevelt.

George Clinton was born in Kannapolis, North Carolina but he formed his first group, a vocal combo called the Parliaments, out of the back room of his Plainfield, New Jersey barbershop in the early 60s. The Parliaments would actually briefly see the light of day during a short-lived contract with Motown. But their lone release saw little attention so, in 1969, the Parliaments disbanded, leaving the name under record company ownership.

Over the course of the 70s, Clinton would consequently preside over not one but two units, each of which helped to define funk at its best, most creative, most tripped out, and most schizophrenic. Funkadelic’s gritty psychedelic soul served as a blueprint both for the conceptual approach to record-making and the sharp-tongued street journalism that would eventually shape hip-hop. If Funkadelic’s legacy wasn’t enough on its own, Clinton also diverted half of his attention to Parliament in the mid-70s.

Even as Funkadelic was writing the psychedelic soul bible on albums like Maggot Brain (1971), Cosmic Slop (1973), and Hardcore Jollies (1976), Parliament would set the mold for grimy, horn-heavy funk on records like Up For the Down Stroke (1974), Chocolate City (1975), and Mothership Connection (1975). Taken together, Parliament-Funkadelic created a mind-blowing live experience in which as many as 50 musicians might crowd the stage with glorious color and noise.

With 1978’s Funkadelic release, One Nation Under a Groove, Clinton achieved a masterpiece of confluence, the moment of greatest mainstream visibility for Funkadelic and the record on which all the moving parts in the Clinton kingdom came together. One Nation emerged on the back side of the funk movement, in the midst of the disco boom, and as a prelude to hip-hop. This is Clinton’s commercial and political manifesto, calling for global unity around the impulse to boogie. Clinton solidified his status as a patron saint of hip hop through his much-celebrated early 90s collaborations with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. Both cite Clinton as a seminal influence.

Today, Clinton continues to tour off and on with various members of his P-Funk All-Stars and is a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

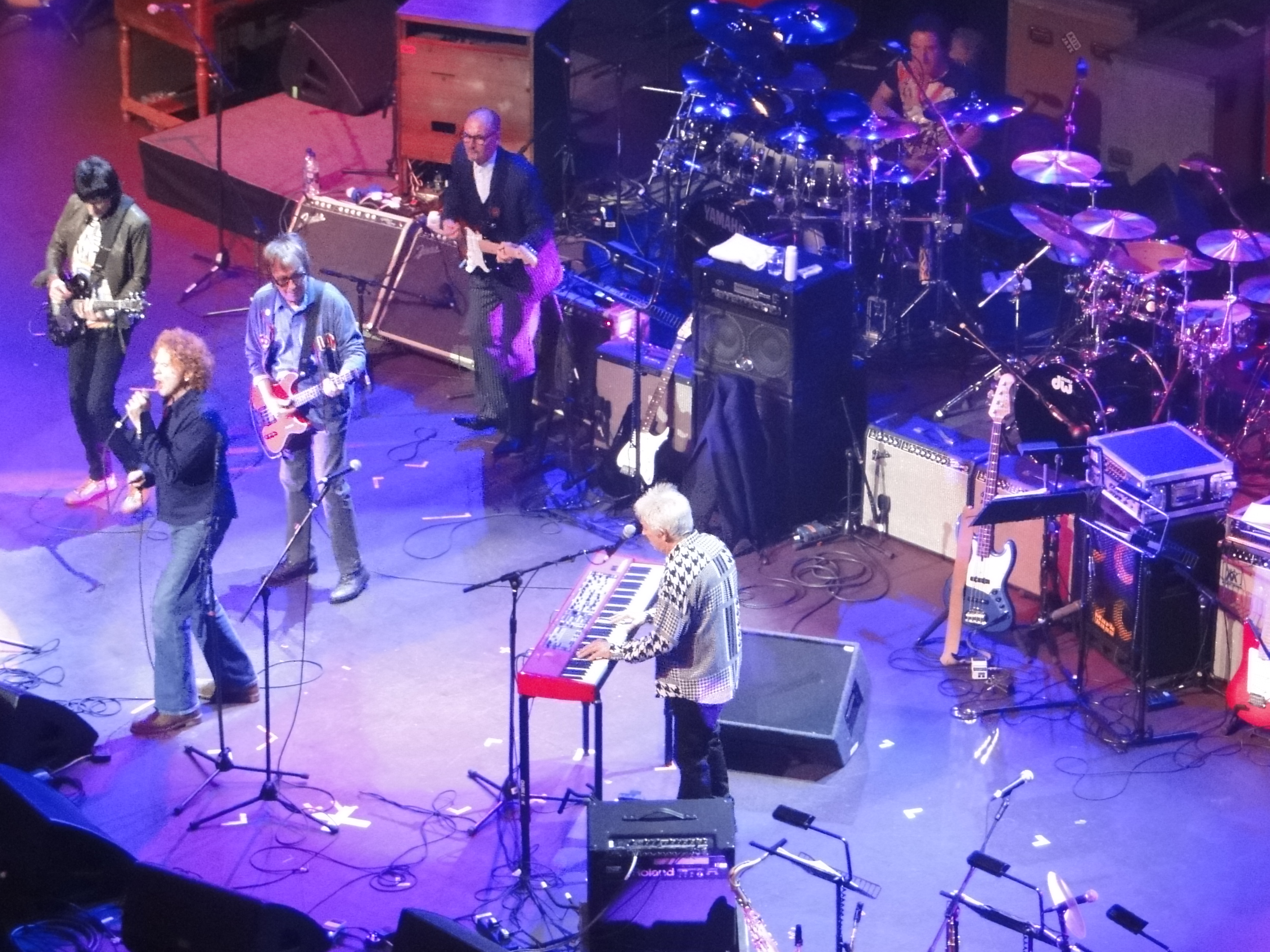

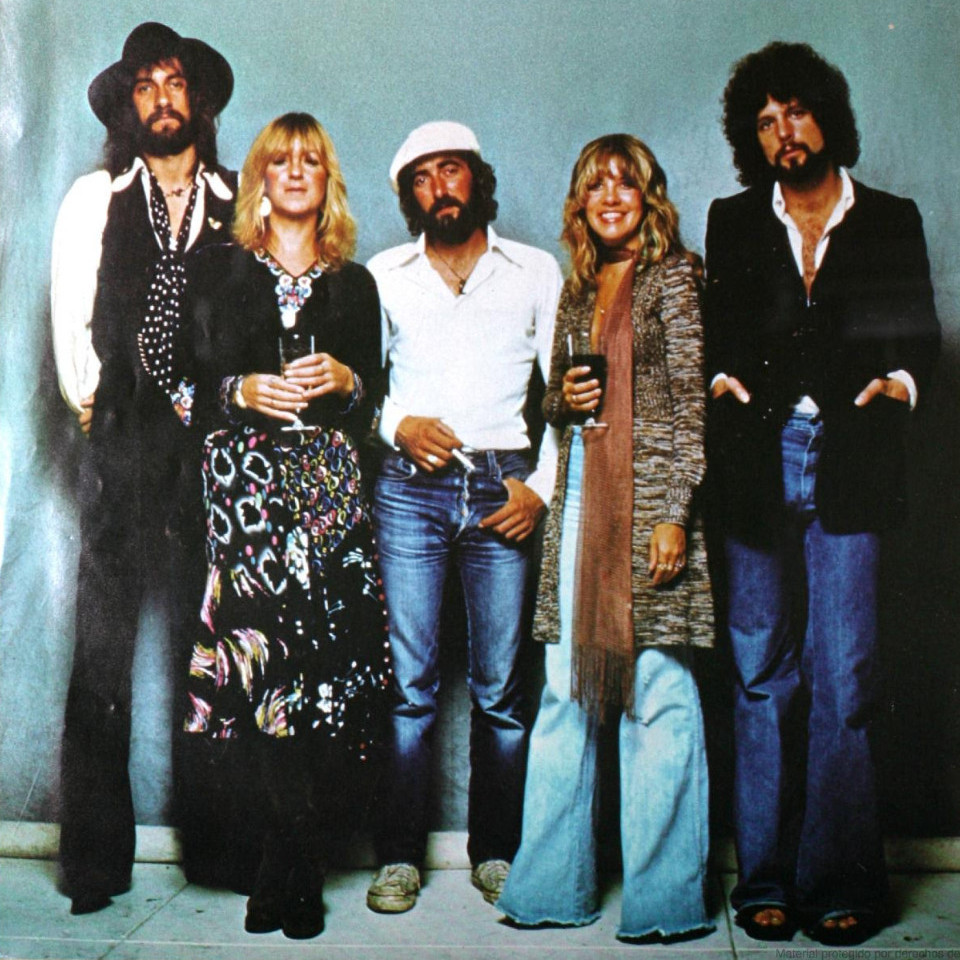

32. Fleetwood Mac

Few bands have transformed more dramatically or more frequently than has Fleetwood Mac. Even fewer have enjoyed their level of success. The band’s lineup has seen dramatic shifts in personnel over more than 50 years and its sound has transformed just as dramatically. Today, the only truly constant member of the group from its first performance to its most recent public appearances has been drummer Mick Fleetwood (with bassist John McVie only joining after the band’s first live show). From its first murmuring as a pure British blues band to its world dominance as the premier pop band of the 1970s, Fleetwood Mac’s is a story of heady success and elegant heartbreak.

The band’s story begins, like most British beat boom stories, deeply entangled with the fate of other future legends. When Eric Clapton departed John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers to form Cream, young guitar stud Peter Green stepped in, forming a backing band with Fleetwood and McVie. After cutting a record behind Mayall, the elder statesman of British blues gifted a few hours of free studio time to his backing band. They made the most of it, producing a series of 1967 recordings under the portmanteau Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac.

Over the next four years, Fleetwood Mac would become one of the scene’s more consistent working class blues combos, even scoring a #1 UK hit with “Albatross” not to mention recording the original “Black Magic Woman,” later covered to far greater notoriety by Santana. This first phase fizzled to an end in 1971 when Peter Green, made increasingly fragile by a combination of mental illness and LSD, departed the band.

This began a period of transition in which various members entered and exited the fray, including guitarists Danny Kirwin and Jeremy Spencer, the former of which would be fired for alcohol-induced excess and the latter of which would disappear only moments before a scheduled concert engagement to join a religious cult. Other additions during this phase were Christine Perfect, who would soon marry the group’s bassist and take the name McVie, and Bob Welch, whose pop sensibility would begin to move the band away from its pure blues roots.

The band’s greatest success was still on the horizon though. With the departure of Welch in 1974, Fleetwood and the McVies recruited guitarist Lindsey Buckingham, who insisted the band also hire his girlfriend, Stevie Nicks. This new five-piece incarnation of Fleetwood Mac released its self-titled debut in 1975 and immediately scored a #1 record, selling five million copies on the strength of Christine McVie’s “Over My Head” and Nicks’s “Rhiannon.” The latter also helped to establish Stevie’s singular stardom within the band, indulging in the Celtic and gypsy imagery that would come to be closely identified with the Arizona-born singer.

Fleetwood Mac’s mid-career eponymous release would mark a new phase in its sound and success. Gone was any evidence of the band’s roots in the blues. In its place was a band capable of shimmering and bittersweet pop music and, consequently, one that found itself suddenly famous in the US. This fame was nothing compared to what was on the immediate horizon. In 1977, the band released Rumours. No fewer than seven of the eleven songs on the record became radio staples, propelling Rumours to the top of the charts before eventually selling 40 million copies. Only the mighty Thriller and the Eagles’ first volume of greatest hits have received more certifications in the US, making it America’s third best selling album of all time.

The album’s story is as much shrouded in darkness as triumph, however. Recorded as the relationships between Nicks and Buckingham, and the McVies, splintered apart, and as Mick Fleetwood proceeded with divorce from his wife (who it happens was George Harrison’s sister-in-law), the emotional anguish is palpable throughout. The supporting tour was marked by the excessive consumption of drugs and alcohol and deeply wrought tension. In the next decade, Fleetwood Mac’s classic lineup would move through various phases of experimentation—such as Tusk (1979)—and popular appeal — like Tango in the Night (1987)—before acrimony led to Buckingham’s departure.

As always, the name would continue on with a host of shifting players, though the classic assembly has gathered together for an array of reunion tours and special engagements in the time since. Fleetwood Mac was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998 and, at present, remains an active touring unit.

Photo By: Warner Bros. Records – Billboard, 25 June 1977, p. 86, Public Domain

31. The Allman Brothers Band

Few things feel more triumphantly American than the Allman Brothers Band, a unit that experienced dramatic and constant personnel shifts through the entirety of its 45 year run but which remained a definitive pillar of both Southern Rock and psychedelic blues. If these two subgenres seem at odds with one another, this may perhaps account for the band’s tumultuous history. A gang of biker hippies led by namesake brothers Duane (guitar) and Gregg (vocals, keyboards), the Allman Brothers formed in Jacksonville, Florida in 1969 around the theretofore untested idea of a band featuring two lead guitarists and two drummers.

Accordingly, the original lineup included Dickey Betts (guitar), Berry Oakley (bass), Butch Trucks (drums), and Jaimoe Johanson (drums). Signing to the fledgling Capricorn label and relocating to its headquarter city of Macon, Georgia, the band began its longstanding association with the region, the state of Georgia, and its omnipresent peach iconography.

The Allmans attracted their fair share of inhospitable attention in the not-particularly-integrated city of Macon, both for their long hair and the inclusion of a Black bandmate in Johanson. But their rising profile as a live performing act also attracted scores of young Southern rock acts to Macon, creating a new hotbed for a genre that would soon dominate FM radio playlists.

On their first two albums, The Allman Brothers Band (1969) and Idlewild South (1970), the Brothers experienced disappointing commercial returns but their signature sound was already in full bloom. Combining their dusty blues roots with elaborate and extensive instrumental workouts, the Allman Brothers were quietly earning a reputation as a virtuosic pack of acid-scarfing troublemakers, kind of like the southland’s own Grateful Dead. Duane, in particular, gained increasing industry recognition as the finest slide-guitar player in the business, a title further cemented by his collaboration with Eric Clapton on Derek and the Dominoes and their immortal “Layla” in 1970.

The following year, recognizing the legend growing around their live show, the Allman Brothers recorded 1971’s At the Fillmore East, a sprawling double LP showcasing the band’s incendiary performance chops. Fillmore catapulted the Brothers to superstardom and solidified them as one of the most important touring acts of the decade. Arguably, in the post-Woodstock era, the Allman Brothers would be matched only by the Dead in their undying commitment to the ever-burning hippie flame of peace, love, and psilocybin mushrooms.

By late ’71, the Allmans were at the height of their popularity, but heroin had reared its ugly head within the band’s ranks. Berry Oakley and Duane himself had developed deep dependencies and, by October, had both entered rehabilitation. Sadly, on the day of his return from treatment, Duane was killed in a motorcycle crash. The loss devastated the tightly-knit outfit but they chose to journey on in their fallen leader’s honor. In ’72, the band accomplished the rare feat (probably never to be equaled), of releasing a second consecutive gold selling double LP. Eat a Peach reinforced the band’s staying power even without its spiritual and musical director.

Guitarist Dicky Betts tacitly stepped into the lurch and led the group through its next stage. Sadly, a second consecutive hit record would be tarnished by tragedy when, almost exactly one year later, in nearly the exact same geographical location, Berry Oakley lost his life in a motorcycle crash that was startlingly similar in nature to that which claimed his friend and bandmate.

With Betts at the helm, the band added new members and continued its ascension, scoring an unlikely #2 hit in 1973 with “Ramblin’ Man.” Nonetheless, drug abuse and tension fractured the band and disrupted the unity that had once defined it, leading to a particularly fractious relationship between Gregg and Dicky Betts.

Splitting for the first time in 1976, the Allmans reunited frequently, if not always happily, over the next several years. During the coming decade, however, their recorded output was inconsistent, as was their general desire to be on the road or around one another. Particularly alienated by industry pressure to modernize their stalwart blues-rock sound and image, the band largely faded from relevance until 1989. Energized by the benefit of backward looking classic rock radio formats and a jam band revival spearheaded by upstarts like Phish and Blues Traveler, the Allman Brothers were readily embraced by a new generation of longhairs.

Over the next several decades, the Allmans made their permanent home on the road, touring endlessly in various incarnations within which only Gregg was a constant presence. The Allmans remained steadfastly committed to the jam scene as the bands around them got younger, even becoming a launchpad for other genre stars like Govt Mule’s Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks, the guitar-slinging virtuoso nephew of drummer Butch. Among the band’s most beloved traditions was its annual month-long stand at New York’s legendary Beacon Theatre, where it holds the distinction of having sold out 238 consecutive shows.

Rock and Roll Hall of Famers and owners of 11 Gold and five Platinum records, the Allmans played their very last show in 2014. Gregg Allman passed away in 2017, marking the true end to one of rock’s greatest journeys.

30. The Doors