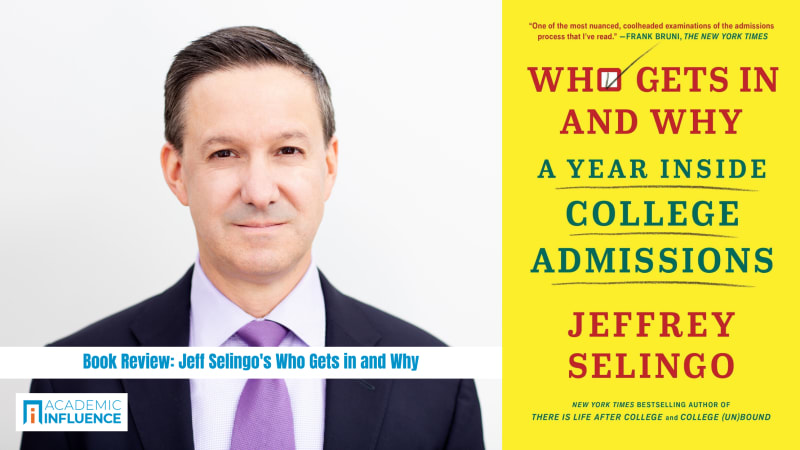

Book Review: Jeff Selingo’s Who Gets In & Why — A Year Inside College Admissions

College admissions is a numbers game—rising tuition, shrinking admission rates, and the big business of college ranking. But how well do students and families really understand the behind-the-scenes calculations that control their fate? In his newest book, Arizona State University professor and author Jeffrey Selingo calls the college admissions process “probably the most mysterious, misunderstood, and debated aspect of American higher education, and maybe its most important function.” (Pg. 5)

The college admissions process is the subject at the heart of Selingo’s newest investigation, Who Gets In and Why-A Year Inside College Admissions (2020; Scribner). The author spent seven months embedded in three very different college admissions offices. Here, he channels his observations into an eye-opening discussion on a deeply imperfect admissions system. Critique courses through Selingo’s research. But the goal of his book is not to decry the current admissions system. Rather, he provides students and families with a guided tour through the hidden offices, conference rooms, and conversations that shape each student’s prospects of admission. In doing so, Selingo peels the cover off of more than a few of higher education’s dirty little secrets.

Jeffrey Selingo’s background provides for a unique perspective on the subject matter. In addition to his role as a special adviser and professor of practice at Arizona State, Selingo brings two decades as a writer and editor for Washington Post, The Atlantic, and The Chronicle of Higher Education to his research. However, it is his early work for leading college ranker U.S. News & World Report (USNWR) that is especially compelling here. It was from this vantage, in the early 1990s, that Selingo watched as student applications skyrocketed, and admission rates shrunk precipitously. It was from this position that he witnessed the growing emphasis on selectivity, and that he perceived the shifting winds in higher education.

Increasingly, suggests Selingo, we have come to conflate selectivity with excellence. This error in thinking necessitates Selingo’s exposé, which simultaneously breaks down the sobering reality of just how exclusive America’s top schools really are and provides comforting reassurance that there are so many other ways to enjoy a meaningful college experience. In this regard, Selingo’s book is at once highly effective and perhaps even a little therapeutic to the vast majority of students who will likely never attend one of America’s elite universities. The central premise of Selingo’s book seems to be that students aren’t necessarily rejected from their dream colleges because of some critical deficiency. The reality, argues Selingo, is that so much of the admissions process is random, impersonal, and driven by abstract university priorities rather than student profiles.

How Admissions Really Work

The insight that Selingo provides here comes from three very different admissions processes. Selingo notes that “I was with the staff at the University of Washington as they were trained to read admissions files. I went to Davidson College in North Carolina to see counselors debate, applicant by applicant, whom to admit for early decision. And I examined the details of applications alongside pairs of readers in their offices at Emory University and listened as they weighed their choices.” (p. 4)

The goal of Selingo’s text is to demystify these hidden processes for students and their families while also shining a light on some of the fundamental flaws in the college admissions “machine.” For instance, Selingo calls out the leading college ranking systems like his former employer. U.S. News & World Report rankings, Selingo argues, have an outsized impact on student perceptions, university decisions, and the all-important admissions rate. And yet, it’s not clear that these rankings do an effective job of measuring what students want, or telling them what they need to know before choosing a college.

The Exclusivity of College Ranking

Selingo observes that

When a top school drops in the rankings, it's forced to admit more students in subsequent years and is more generous with financial aid to make up for falling yield rates, according to a study for the National Bureau of Economic Research. Clearly students use the rankings to put some semblance of order to a chaotic process. But the rankings, in large part, also give prospective students a narrow lens on the college search: they don't look up and out beyond the top 10 or 20.” – (pg. 77-78)

Selingo suggests that such rankings do not effectively deliver on the promise of matching students with the best schools for them. But this is not an accident, he argues. For elite colleges, a growing number of submitted applications, paired with an unchanging number of available slots, equals a shrinking admission rate. This type of selectivity is a metric widely equated with educational excellence. Selingo puts this in context with a telling statistic. He points out that “the most selective institutions-representing only 20 percent of American colleges-account for about one-third of all applications submitted.” (p. 39)

Naturally, schools with this type of selectivity are most consistently represented in the highly-publicized annual “best colleges” rankings. Selingo’s closer examination reveals that admission rate figures are arbitrary at best, and untruthful at worst. In fact, we recently had the opportunity recently to speak with the author about this background as USNWR.

Gaming the Competition

We enjoyed a fascinating exchange that touched on many aspects of his new book. During our conversation, he recalled from his days with the leading college ranker that “We used to laugh that with a keystroke or two, we could actually probably change the rankings of a bunch of colleges. But that was yet another thing that gave me insight into admissions.”

This speaks to the arbitrary nature of rankings. Selingo’s book also emphasizes the randomness of college admissions. The sheer number of nearly identical applicants that admissions offices must evaluate and the limited number of available spots at elite schools leads to a process that is, to an extent, arbitrary and random by design. Growing selectivity is not necessarily an indication that the standards for admission have grown more stringent, nor does it necessarily denote greater excellence in the new crop of first-year students. It does, however, indicate that many deserving candidates must be rejected for reasons which are either impersonal or impossible to quantify.In some instances, Selingo reveals, those reasons are rooted in systemic realities that go far beyond the profile of any one student. For instance, Selingo reveals that

The preference given to the sons and daughters of alumni is nearly ubiquitous in elite higher education. Few schools, however, like to talk about legacy admissions or publicize acceptance rates for the children of alumni.” – (p. 159)

The truth, however, is that competition for the precious few spots at the most elite universities is tilted deeply in favor of those legacies. Selingo notes that between 2009 and 2015, Harvard University boasted a 6% acceptance rate to the general population, whereas legacies were admitted at a rate of 34%. Most years, says Selingo, one-third of a Harvard freshman class is made up of legacies. (p. 159)

Selingo points to other factors like the deep but largely unspoken advantage enjoyed by students attending certain high schools. He references a study by admissions consulting firm Human Capital Research that analyzed 130,000 applications to a brand-name college over the course of a decade. Findings revealed that just 18 percent of high schools produced “75 percent of applications and 79 percent of admitted students.” (p. 164)

This, says Selingo, is true across the higher education landscape. Indeed, many admissions offices begin the evaluation process by sorting applicants according to high school (as opposed to individual merit).

Ranking–The Illusion of Excellence

These are institutional realities over which students have little or no control. This, to an extent, is what makes traditional rankings so problematic, and even potentially injurious. The visibility of, and emphasis on, ranking lists provides a misleading and partial view of the higher education landscape. This view can be damaging and discouraging to students who would be better served by a realistic set of measures and a more accessible range of high quality education options.

During our conversation, Selingo observed that

The top 50 colleges...they have limited seats for all the students trying to apply to them. So I think you have to start from the beginning and realize that your chances of getting into one of these highly selective colleges...it's tough. And so I think that you should kind of go in... If you go into it with that process, that those are some of your reach schools, but that you're going to find places that are going to be a good academic and social fit, I think that's to me, that's the key to a good college search. Because there are many staging grounds throughout life, and college is one of them. But as I point out in the book, it's not the only one.”

The positive takeaway, both from Selingo’s book, and from our conversation, is that college remains a valuable and accessible option for most applicants. He points out during our discussion that “the average acceptance rate of a college is 65%, so most kids get into college.”

This suggests a level of access that is often obscured by our emphasis on highly selective schools. “And,” says Selingo, “it’s true that because these highly selective schools are getting more applicants than ever before, they’re denying more kids than ever before.”

Choose Compatability Over Selectivity

But Selingo’s central argument is an optimistic one-that prospective students have numerous accessible options for a high quality education. By mistaking selectivity for educational excellence, we risk creating unrealistic expectations, both for students who are unlikely to gain entry into highly selective schools and for those who might be disappointed by what they experience when they do get in.

“Prospective students should then follow the lead of these selective schools and widen their own playing field to include colleges that will actually accept them,” Says Selingo. “There are plenty of good schools that take a majority of students who apply. A student can only attend one college at a time, so there’s no reason to apply to seven top schools. Parents and counselors need to do better to show seniors that there are more colleges out there than just those listed on the first page of the U.S. News rankings.” (p. 264)

Naturally, rankings will continue to influence the way colleges behave, and how students make critical decisions. But Selingo offers a sage bit of advice to those embarking on their college search. While many popular rankings trumpet prestige or simply reinforce existing hierarchies in higher education, “The best college searches are those that help applicants discover themselves on their way to becoming adults.” (p. 55)

Learn more with a look at our Guide to the College Admissions Process.

Or get tips on studying, student life, and much more with a look at our Student Resources.